T RANSITION , C HANGE , AND THE

R OAD TO W AR , 1902–1917

or the United States the opening years of the twentieth century were a time of transition and change. At home it was a period of social change, often designated the Progressive Era, when political

leaders such as President Theodore Roosevelt undertook to solve the economic and social problems arising out of the rapid growth of large-scale industry in the late nineteenth century. Increasing public awareness of these problems as a result of the writings of the "Muckrakers" and social reformers provided popular support for efforts to solve them by legislative and administrative measures. In foreign affairs it was a period when the country had to begin adjusting its institutions and policies to the requirements of its new status as a world power with imperial responsibilities. In spite of a tendency after the end of the War with Spain to follow traditional patterns and go back to essentially isolationist policies, the nation’s new responsibility for overseas possessions, its expanding commercial interests abroad, and the continued unrest in the Caribbean made a reversion to insularity increasingly unfeasible.

The changing conditions at home and abroad inevitably affected the nation’s military establishment. During the decade and a half between the War with Spain and American involvement in World War I, both the Army and the Navy would undergo important reforms in organization and direction. Although the United States did not participate in any major conflict during these years, both services were frequently called upon to assist with administration of newly acquired possessions overseas. Both aided with protection of investments abroad threatened by native insurrections, revolutions, and other internal disturbances. And both contributed in other ways to upholding the vital interests of the nation in an era of greatly increased competition for commercial advantage and colonial empire. Much of the experience gained in the decades of the Indian Wars was used to great advantage in the essentially

By the early years of the twenti-

eth century the increasingly com-

plex network of agreements had

resulted in a new and precarious

balance of power in world affairs.

constabulary duties required to police an empire, but much needed to be done to modernize the military and prepare it for its new role in world affairs.

Modernizing the Armed Forces

The intensification of international rivalries led most of the Great Powers to seek additional protection and advantage in diplomatic alliances and alignments. By the early years of the twentieth century the increasingly complex network of agreements had resulted in a new and precarious balance of power in world affairs. This balance was constantly in danger of being upset, particularly because of an unprecedented arms race characterized by rapid enlargement of armies and navies and development of far more deadly weapons and tactics. While the United States remained aloof from such "entangling alliances," it nevertheless continued to modernize and strengthen its own armed forces, giving primary attention to the Navy—the first line of defense.

The Navy’s highly successful performance in the Spanish-American War increased the willingness of Congress and the American public to support its program of expansion and modernization. For at least a decade after the war Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, and other leaders who favored a "Big Navy" policy with the goal of an American fleet second only to that of Great Britain had little difficulty securing the necessary legislation and funds for the Navy’s expansion program.

For the Navy another most important result of the War with Spain was the decision to retain possessions in the Caribbean and the western Pacific. In the Caribbean, the Navy acquired more bases for its operations such as that at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. The value of these bases soon became apparent as the United States found itself intervening more frequently in the countries of that region to protect its expanding investments and trade. In the long run, however, acquisition of the Philippines and Guam was even more significant, for it committed the United States to defense of territory thousands of miles from the home base. American naval strength in the Pacific had to be increased immediately to ensure maintenance of a secure line of communications for the land forces that had to be kept in the Philippines. One way to accomplish this increase, with an eye to economy of force, was to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama to allow Navy ships to move more rapidly from the Atlantic to the Pacific as circumstances demanded. Another was to acquire more bases in the Pacific west of Hawaii, which was annexed in 1898. Japan’s spectacular naval victories in the war with Russia and Roosevelt’s dispatch of an American fleet on a round-the-world cruise from December 1907 to February 1909 drew public attention to the problem. But most Americans failed to perceive Japan’s growing threat to U.S. possessions in the western Pacific, and the line of communications to the Philippines remained incomplete and highly vulnerable.

The Navy worked hard to expand the fleet and incorporate the latest technological developments in ship design and weapons. The modernization program that had begun in the 1880s and had much to do with the Navy’s effectiveness in the Spanish-American War continued

in the early 1900s. Construction of new ships, stimulated by the war and Roosevelt’s active support, continued at a rapid rate after 1898 until the Taft administration and at a somewhat slower pace thereafter. By 1917 the United States had a Navy unmatched by any of the Great Powers except Great Britain and Germany.

The Army, aware of the serious deficiencies revealed in the War with Spain and of the rapid technological changes taking place in the methods of warfare, also undertook to modernize its weapons and equipment. Development of high-velocity, low-trajectory, clip-loading rifles capable of delivering a high rate of sustained fire had already made obsolete the Krag-Jörgensen rifle, which the Army had adopted in 1892. In 1903 the Regular Army began equipping its units with the improved bolt-action, magazine-type Springfield rifle, which incorporated the latest changes in weapons technology. The campaigns of 1898 also had shown that the standard rod bayonet was too flimsy; starting in 1905, the Army replaced it with a sturdy knife bayonet. The 1906 addition of a greater propellant charge in ammunition for the Springfield provided even higher muzzle velocity and deeper penetration of the bullet. Combat at close quarters against the fierce charges of the Moros in the Philippines demonstrated the need for a hand weapon less cumbersome and having greater impact than the .38-caliber revolver. The Army found the answer in the recently developed .45-caliber Colt automatic pistol, adopted in 1911, that was to remain a mainstay of the Army for most of the rest of the century.

Far more significant in revolutionizing the nature of twentieth century warfare than these improved hand weapons was the rapid-firing machine gun. The manually operated machine gun—the Gatling gun—which the Army had adopted in 1866, was employed successfully in the Indian Wars and the Spanish-American War. American inven-

Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911. Browning’s self-loading pistol had a detachable seven-round magazine.

tors, including Hiram Maxim, John Browning, and Isaac N. Lewis, the last an officer in the Army’s coast artillery, took a leading part in developing automatic machine guns in the years between the Civil War and World War I. Weapons based on their designs were adopted by many of the armies of the world. But not until fighting began in World War I would it be generally realized what an important role the machine gun was to have in modern tactics. Thus, in the years between 1898 and 1916, Congress appropriated only an average of $150,000 annually for procurement of machine guns, barely enough to provide four weapons for each regular regiment and a few for the National Guard. Finally in 1916 Congress voted $12 million for machine-gun procurement, but the War Department held up its expenditure until 1917 while a board tried to decide which type of weapon was best suited to the needs of the Army.

Development of American artillery and artillery ammunition also lagged behind that of west European armies. The Army did adopt in 1902 a new basic field weapon, the three-inch gun with an advanced recoil mechanism. Also, to replace the black powder that had been the subject of such widespread criticism during the War with Spain, both the Army and the Navy took steps to increase the domestic output of smokeless powder. By 1903 production was sufficient to supply most American artillery for the small Regular Army.

Experience gained in the Spanish-American War also brought some significant changes in the Army’s coastal defense program. The hurriedly improvised measures taken during the war to protect Atlantic ports from possible attack by the Spanish Fleet emphasized the need for modern seacoast defenses. Under the strategic concepts in vogue, construction and manning of these defenses were primarily Army responsibilities since in wartime the naval fleet had to be kept intact, ready to seek out and destroy the enemy’s fleet. On the basis of recommendations by the Endicott Board, the Army already had begun an ambitious coastal defense construction program in the early 1890s. In 1905 a new board headed by Secretary of War William Howard Taft made important revisions in this program with the goal of incorporating the latest techniques and devices. Added to the coastal defense arsenal were fixed, floating, and mobile torpedoes and submarine mines. At the same time the Army’s Ordnance Department tested new and more powerful rifled artillery for installation in the coastal defense fortifications in keeping with the trend toward larger and larger guns to meet the challenge of naval weapons of ever-increasing size.

Of the many new inventions that came into widespread use in the early twentieth century in response to the productive capacity of the new industrial age, none was to have greater influence on military strategy, tactics, and organization than the internal combustion engine. It made possible the motor vehicle, which, like the railroad in the previous century, brought a revolution in military transportation, and the airplane and tank, both of which would figure importantly in World War I. The humble internal combustion engine was not as exciting or as dramatic a development as the machine gun or a new type of howitzer, but its long-term impact changed the face of warfare and made possible the huge mechanized formations that were to dominate war in the latter half of the twentieth century.

"I took the United States for my client," said seasoned New

York attorney Elihu Root (1845−1937) of his accession as Secre-

tary of War in 1899. Having been denied enlistment in the Union

Army because of poor health, he was not a veteran. Yet despite his

initial unfamiliarity with military affairs, Secretary Root initiated some

of the most significant Army reforms of the twentieth century. He

subsequently served as Secretary of State and U.S. Senator. For his

War Department role in administering Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the

Philippines acquired in the Spanish-American War, and his work as

Secretary of State on U.S. relations with Japan and Latin America,

he received the Nobel Peace Prize for 1912.

Elihu Root,

Secretary of War, 1899–1904

Raimundo de Madrazo, 1907

Reorganization of the Army

Establishment of the General Staff

After the Spanish-American War the Army also underwent important organizational and administrative changes aimed in part at overcoming some of the more glaring defects revealed during the war. Although the nation had won the war with comparative ease, many Americans realized that the victory was attributable more to the incompetence of the enemy than to any special qualities displayed by the Army. In fact, as a postwar investigating commission appointed by President William McKinley and headed by Maj. Gen. Granville M. Dodge brought out, there was serious need for reform in the administration and direction of the Army’s high command and for elimination of widespread inefficiency in the operations of the War Department.

No one appreciated the need for reform more than Elihu Root, a New York lawyer whom McKinley appointed Secretary of War in 1899. The President had selected Root primarily because he seemed well qualified to solve the legal problems that would arise in the Army’s administration of recently acquired overseas possessions. But Root quickly realized that if the Army was to be capable of carrying out its new responsibilities as an important part of the defense establishment of a world power, it had to undergo fundamental changes in organization, administration, and training. Root, as a former corporation lawyer, tended to see the Army’s problems as similar to those faced by business executives. "The men who have combined various corporations … in what we call trusts," he told Congress, "have reduced the cost of production and have increased their efficiency by doing the very same thing we propose you shall do now, and it does seem a pity that the Government of the United States should be the only great industrial establishment that cannot profit by the lessons which the world of industry and of commerce has learned to such good effect."

Beginning in 1899, Root outlined in a series of masterful reports his proposals for fundamental reform of Army institutions and concepts to achieve that "efficiency" of organization and function required of

armies in the modern world. He based his proposals partly upon recommendations made by his military advisers (among the most trusted were Adjutant General Maj. Gen. Henry C. Corbin, and Lt. Col. William H. Carter) and partly upon the views expressed by officers who had studied and written about the problem in the post–Civil War years. Root arranged for publication of Col. Emory Upton’s The Military Policy of the United States (1904), an unfinished manuscript that advocated a strong, expansible Regular Army as the keystone of an effective military establishment. Concluding that after all the true object of any army must be "to provide for war," Root took prompt steps to reshape the American Army into an instrument of national power capable of coping with the requirements of modern warfare. This objective could be attained, he hoped, by integrating the bureaus of the War Department, the scattered elements of the Regular Army, and the militia and volunteers.

Root perceived as the chief weakness in the organization of the Army the long-standing division of authority, dating back to the early nineteenth century, between the Commanding General of the Army and the Secretary of War. The Commanding General exercised discipline and control over the troops in the field; while the Secretary, through the military bureau chiefs, had responsibility for administration and fiscal matters. Root proposed to eliminate this division of authority between the Secretary of War and the Commanding General and to reduce the independence of the bureau chiefs. The solution, he suggested, was to replace the Commanding General of the Army with a Chief of Staff, who would be the responsible adviser and executive agent of the President through the Secretary of War. Under Root’s proposal, formulation of broad American policies would continue under civilian control.

A lack of any long-range planning by the Army had been another obvious deficiency in the War with Spain, and Root proposed to overcome this by the creation of a new General Staff, a group of selected officers who would be free to devote their full time to preparing military plans. Planning in past national emergencies, he pointed out, nearly always had been inadequate because it had to be done hastily by officers already overburdened with other duties. Pending congressional action on his proposals, Root in 1901 appointed an ad hoc War College Board to act as an embryonic General Staff. In early 1903, in spite of some die-hard opposition, Congress adopted the Secretary of War’s recommendations for both a General Staff and a Chief of Staff but rejected his request that certain of the bureaus be consolidated.

By this legislation Congress provided the essential framework for more efficient administration of the Army. Yet legislation could not change overnight the long-held traditions, habits, and views of most Army officers or of some congressmen and the American public. Secretary Root realized that effective operation of the new system would require an extended program of reeducation. This need for reeducation was one important reason for the establishment of the Army War College in November 1903. Its students, already experienced officers, would receive education in problems of the War Department and of high command in the field. As it turned out, they actually devoted much of their time to war planning, becoming in effect the part of the General Staff that performed this function.

In the first years after its establishment the General Staff achieved relatively little in the way of genuine staff planning and policy making. While staff personnel did carry out such appropriate tasks as issuing in 1905 the first Field Service Regulations for government and organization of troops in the field, drawing up the plan for an expeditionary force sent to Cuba in 1906, and supervising the Army’s expanding school system, far too much of their time was devoted to day-to-day routine administrative matters.

The General Staff did make some progress in overcoming its early weaknesses. Through experience, officers assigned to the staff gradually gained awareness of its real purpose and powers. In 1910, when Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood became Chief of Staff, he reorganized the General Staff, eliminating many of its time-consuming procedures and directing more of its energies to planning. With the backing of Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson (1911–1913), Wood dealt a decisive blow to that element in the Army itself that opposed the General Staff. In a notable controversy, he and Stimson forced the retirement in 1912 of the leader of this opposition, Maj. Gen. Fred C. Ainsworth, The Adjutant General.

The temporary closing of most Army schools during the Spanish-American War and the need to coordinate the Army’s educational system with the Root proposals for creating a War College and General Staff had provided an opportunity for a general reorganization of the whole system, with the overall objective of raising the standards of professional training of officers. In 1901 the War Department directed that the schools of instruction for officers thereafter should be the Military Academy at West Point; a school at each post of elementary instruction in theory and practice; the five service schools (the Artillery School, Engineer School of Application, School of Submarine Defense [mines and torpedoes], School of Application for Cavalry and Field Artillery, and Army Medical School); a General Staff and Service College at Fort Leavenworth; and a War College. The purpose of the school at Leavenworth henceforth was to train officers in the employment of combined arms and prepare them for staff and command positions in large units. To meet the requirements for specialized training as a result of new developments in weapons and equipment, the Army expanded its service school system, adding the Signal School in 1905, the Field Artillery School in 1911, and the School of Musketry in 1913.

Creation of the General Staff unquestionably was the most important organizational reform in the Army during this period, but there were also a number of other changes in the branches and special staff designed to keep the Army abreast of new ideas and requirements. The Medical Department, for example, established Medical, Hospital, Army Nurse, Dental, and Medical Reserve Corps. In 1907 Congress approved the division of the artillery into the Coast Artillery Corps and the Field Artillery and in 1912 enacted legislation consolidating the Subsistence and Pay Departments with the Quartermaster to create the Quartermaster Corps, a reform Secretary Root had recommended earlier. The act of 1912 also established an enlisted Quartermaster service corps, marking the beginning of the practice of using service troops instead of civilians and combat soldier details.

In the new field of military aviation, the Army failed to keep pace with early twentieth century developments. Contributing to this delay

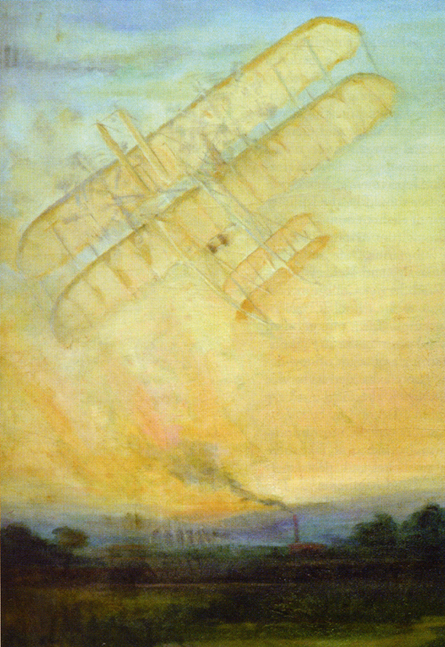

T HE A RMY AND THE W RIGHT B ROTHERS

On July 30, 1909, a frail biplane sporting a 24-horsepower engine took off from the parade ground

at Fort Myer, Virginia. Orville Wright was at the controls with Lt. Benjamin D. Foulois aboard as a passen-

ger-observer. This was the third and final test to see if the flyer, as Orville and his brother Wilbur referred

to their machine, satisfied the War Department’s specifications for a military "aeroplane." In slightly more

than twenty-eight minutes they returned, having traveled an average speed of 42.583 miles per hour over a

measured course. The U.S. Army Signal Corps purchased the world’s first military aircraft for $30,000.

Wright Bros. Experimental Military Aircraft, Imra Maduro Peixotto, 1909

were the reluctance of Congress to appropriate funds and resistance within the military bureaucracy to the diversion of already limited resources to a method of warfare as yet unproved. The Army did not entirely neglect the new field—it had used balloons for observation in both the Civil and Spanish-American Wars and, beginning in 1898, the War Department subsidized for several years Samuel P. Langley’s experiments with power-propelled, heavier-than-air flying machines. In 1908, after some hesitation, the War Department made funds available to the Aeronautical Division of the Signal Corps (established a year earlier) for the purchase and testing of Wilbur and Orville Wright’s airplane. Although the Army accepted this airplane in 1909, another two years passed before Congress appropriated a relatively modest sum ($125,000) for aeronautical purposes. Between 1908 and 1913, it is estimated that the United States spent only $430,000 on military and naval aviation, whereas in the same period France and Germany each expended $22 million; Russia, $12 million; and Belgium, $2 million. Not until 1914 did Congress authorize establishment of a full-fledged Aviation Section in the Signal Corps. The few military airplanes available for service on the Mexican border in 1916 soon broke down, and the United States entered World War I far behind the other belligerents in aviation equipment, organization, and doctrine.

Reorganization of the Army

The Regular Army and the Militia

In the years after the Spanish-American War nearly a third of the Regular Army troops, on the average, served overseas. Most were in the Philippines suppressing the insurrection and, when that conflict officially ended in mid-1902, stamping out scattered resistance and organizing and training a native force known as the Philippine Scouts. Other regulars were garrisoned in Alaska, Hawaii, China, and elsewhere. To carry out its responsibilities abroad and to maintain an adequate defense at home, the Regular Army from 1902 to 1911 had an average of 75,000 officers and men, far below the 100,000 that Congress had authorized in 1902 to fill thirty infantry and fifteen cavalry regiments supported by a corps of artillery. To make up for this deficiency in size of the regular forces and at the same time to remedy some of the defects revealed in the mobilization for the War with Spain, the planners in the War Department recommended a reorganization of the volunteer forces.

Secretary Root took the lead in presenting to Congress in 1901 a program for reform of the National Guard. In response to his recommendations, Congress in 1903 passed the Dick Act, which thoroughly revised the obsolete Militia Act of 1792. It separated the militia into two classes—the Organized Militia, to be known as the National Guard, and the Reserve Militia—and provided that over a five-year period the Guard’s organization and equipment would be patterned after that of the Regular Army. To help accomplish these changes in the Guard, the Dick Act made federal funds available; prescribed drill at least twice a month, supplemented with short annual training periods; permitted detailing of regular officers to Guard units; and directed the holding of joint maneuvers each year. The new measure failed, however, to significantly modify the longstanding provisions that severely restricted federal power to call up Guard units and control Guard personnel, which limited its effectiveness. Subsequent legislation in 1908 and 1914 reduced these restrictions to some extent, giving the President the right to prescribe the length of federal service and with the advice and consent of the Senate to appoint all officers of the Guard while the Guard was in federal service.

P HILIPPINE S COUTS

A number of locally recruited scout companies were formed during the Philippine Insurrection

(1899−1902) even before the 1901 law that formally authorized their creation as part of the U.S. Army.

Filipinos served as enlisted personnel and NCOs in Philippine Scout units that by 1922 included infantry,

cavalry, and field artillery regiments under an officer corps that remained primarily American even after Fili-

pinos became eligible for commissioning through the U.S. Military Academy in 1914. Trained and equipped

as Regular Army units, they mounted a valiant defense against the Japanese during World War II. Reconsti-

tuted as the New Scouts by the U.S. Armed Forces Voluntary Recruitment Act of 1945, the force continued

to protect American and Filipino interests until its official dissolution in 1950.

The military legislation passed in 1908 contained one additional provision that was to have far-reaching consequences. On April 23, 1908, the creation of the Medical Reserve Corps authorized the placement of several hundred medical personnel on a federal reserve status to be called to active duty if needed to augment the regular medical doctors. This was the small and humble beginning of the U.S. Army Reserve that in the future would train, commission, mobilize, and retain hundreds of thousands of officers. This legislation established the third component of the U.S. Army in addition to the Regular Army and the National Guard. The U.S. Army Reserve was to be a federal reserve, not belonging to the states, which would help provide the basis for the actual implementation of the expansible army theory.

The Creation of Larger Units

Although the largest permanent unit of the Regular Army in peacetime continued to be the regiment, experience in the Spanish-American War, observation of new developments abroad, and lessons learned in annual maneuvers all testified to the need for larger, more self-sufficient units composed of the combined arms. Beginning in 1905, the Field Service Regulations laid down a blueprint for the organization of divisions in wartime, and in 1910 the General Staff drew up a plan for three permanent infantry divisions to be composed of designated Regular Army and National Guard regiments. Because of trouble along the Mexican border in the spring of 1911, the plan was not implemented. Instead, the Army organized a provisional maneuver division and ordered its component units, consisting of three brigades of nearly 13,000 officers and men, to concentrate at San Antonio, Texas. The division’s presence there, it was hoped, would end the border disturbances.

The effort only proved how unready the Army was to mobilize quickly for any kind of national emergency. Assembly of the division required several months. The War Department had to collect Regular Army troops from widely scattered points in the continental United States and denude every post, depot, and arsenal to scrape up the necessary equipment. Even so, when the maneuver division finally completed its concentration in August 1911, it was far from fully operational: none of its regiments were up to strength or adequately armed and equipped. Fortunately, the efficiency of the division was not put to any battle test; and within a short time it was broken up and its component units returned to their home stations. Because those members of Congress who had Army installations in their own districts insisted on retaining them, the War Department was prevented from relocating units so that there would be greater concentrations of troops in a few places. The only immediate result of the Army’s attempt to gain experience in the handling of large units was an effort to organize on paper the scattered posts of the Army so their garrisons, which averaged 700 troops each, could join one of three divisions. But these abortive attempts to mobilize larger units were not entirely without value. In 1913, when the Army again had to strengthen the forces along the Mexican border, a division assembled in Texas in less than a week, ready for movement to any point where it might be needed.

Caribbean Problems and Projects

The close of the War with Spain brought no satisfactory solution for the Cuban problem. As a result of years of misrule and fighting, conditions on the island were deplorable when the war ended. Under provisions of the Teller amendment, the United States was pledged to turn over the rule of Cuba to its people. American forces, however, stayed on to assist the Cubans in achieving at least a modicum of economic and political stability. The first step was to set up a provisional government, headed in the beginning by Maj. Gen. John R. Brooke and later by General Wood. This government promptly undertook a program of rehabilitation and reform. An outstanding achievement was eliminating yellow fever, which had decimated Army troops during the war. Research and experiments carried out by the Army Medical Department culminated in the discovery that a specific type of mosquito transmitted the dread disease. When a concerted effort was generated to control the places where that mosquito bred, the disease was dramatically reduced and the overall improvement in troop health in the tropics was significant.

When order had been restored in Cuba, a constituent assembly met. Under the chairmanship of General Wood, it drew up an organic law for the island patterned after the American Constitution. At the insistence of the United States, this law included several clauses known as the Platt amendment, which also appeared in the subsequent treaty concluded in 1903 by the two countries. The amendment limited the amount of debt Cuba could contract, granted the United States naval bases at Guantanamo and Bahia Honda, and gave the United States the right to intervene to preserve "Cuban independence" and maintain a government "adequate to the protection of life, property and individual liberty." In 1902, after a general election and the inauguration of the republic’s first president, the Americans ended their occupation. But events soon demonstrated that the period of tutelage in self-government had been too short. In late 1906, when the Cuban government proved unable to cope with a new rebellion, the United States intervened to maintain law and order. On the advice of Secretary Taft, President Roosevelt dispatched more than 5,000 troops to Havana, the so-called Army of Cuban Pacification that remained in Cuba until early 1909. Again in 1912 and 1917, the United States found it necessary to intervene but each time withdrew its occupying forces as soon as order was restored. Not until 1934 did the United States, consistent with its new Good Neighbor Policy, give up the right of intervention embodied in the Platt amendment.

The emergence of the United States as a world power with a primary concern for developments in the Caribbean Sea increased the long-time American interest in an isthmian canal. Discovery of gold in California in 1848 and the rapid growth of the West Coast states had underlined the importance of developing a shorter sea route from Atlantic ports to the Pacific. The strategic need for a canal was dramatized for the American people during the Spanish-American War by the 66-day voyage of the battleship Oregon from Puget Sound around Cape Horn to Santiago, where it joined the American Fleet barely in time to participate in the destruction of Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete’s ships.

A few months after the end of the War with Spain, McKinley told Congress that a canal under American control was "now more than ever indispensable." By the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty of 1901, the United States secured abrogation of the terms of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850 that required the United States to share equally with Great Britain in construction and operation of any future isthmian canal. Finally, in 1903, the long-standing question of where to build the canal (Nicaragua or Panama) was resolved in favor of Panama. An uprising in Panama against the government of Colombia provided President Roosevelt with an opportunity to send American naval units to support the rebels, assuring establishment of an independent republic. The new republic readily agreed to permit the United States to acquire control of a ten-mile strip across the isthmus, to purchase the property formerly belonging to the French syndicate that had attempted to construct a canal in the 1880s, and to build, maintain, and operate an interoceanic canal. Congress promptly appropriated the necessary funds for work to begin, and the Isthmian Canal Commission set about investigating the problem of who should construct the canal.

When the commission advised the President that overseeing the construction of so vast a project was beyond the capabilities of any private concern, Roosevelt decided to turn the job over to the Army. He reorganized the commission, assigning to it new members—the majority were Army officers—and in 1907 appointed Col. George W. Goethals as its chairman and chief engineer. In this capacity, Goethals, a graduate of the Military Academy who had served in the Corps of Engineers since 1882, had virtually sole responsibility for administration of the canal project. Displaying great organizational ability, he overcame many serious difficulties, including problems of engineering, employee grievances, housing, and sanitation, to complete the canal by 1914. Goethals owed a part of his success to the support he received from the Army’s Medical Department. Under the leadership of Col. William C. Gorgas,

Construction of Locks for the Panama Canal, April 5, 1913

T HE A RMY , M ALARIA , AND THE P ANAMA C ANAL

William C. Gorgas (1854−1920) headed the Medical Department’s tropical disease program in Pana-

ma. It was one of the world’s great plague regions for yellow fever and malaria; twenty years earlier those

diseases had wrecked a French company’s attempt to construct an interoceanic canal. Gorgas concluded

that malaria posed the greatest danger in Panama. Upon arrival he launched an intensive study of the life

cycle of the carrier, the Anopheles mosquito. His efforts at mosquito abatement eradicated yellow fever but

could only contain malaria. Still the death rate plummeted, removing the medical barrier to the successful

completion of the Panama Canal.

who earlier had played an important role in administering the sanitation program in Cuba, the Army carried through measures to control malaria and virtually wipe out yellow fever, ultimately converting the Canal Zone into a healthy and attractive place to live and work.

The completed Panama Canal stood as a magnificent engineering achievement and an outstanding example of the Army’s fulfillment of a peacetime mission, but its opening and operation under American administration were also highly significant from the point of view of military strategy. For the Navy, the Canal achieved economy of force by eliminating the necessity for maintaining large fleets in both the Atlantic and Pacific. For the Army, it created a new strategic point in the continental defense system that had to be strongly protected by the most modern fortifications manned by a large and well-trained garrison.

The Army on the Mexican Border

Early in the twentieth century the Army found itself frequently involved in hemispheric problems, not only with the countries of the Caribbean region, but also with the United States’ southern neighbor, Mexico. That nation, after a long era of relative political stability, entered a period of revolutionary turmoil. Beginning in 1911, internal conflicts in the northern part of the country led to recurrent incidents along the Mexican border, posing a serious threat to peace. President William Howard Taft first ordered strengthening of the border patrols and then, in the summer of 1911, concentration of the maneuver division at San Antonio. After a period of quiet, General Victoriano Huerta in 1913 deposed and replaced President Francisco Madero. The assassination of Madero shortly thereafter led to full-scale civil war between Huerta’s forces and those of General Venustiano Carranza, leader of the so-called Constitutionalists, and Emiliano Zapata, chief of the radicals. Woodrow Wilson, who had succeeded Taft as President, disapproved of the manner in which Huerta had come to power. In a significant shift from traditional American policy, the President decided not to recognize Huerta on the grounds that his assumption of power did not meet the test of "constitutional legitimacy." At the same time, Wilson imposed an arms embargo on both sides in the civil war. But in early 1914, when Huerta’s forces halted the Constitutionalists, Wilson endeavored to help Carranza by lifting the embargo.

Pancho Villa (1878−1923) was an inspired leader of cavalry in the early years of the Mexican Revolu-

tion. Beginning in 1914, however, he lost a series of battles to President Carranza’s well-trained forces. Villa

raided Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916, hoping to provoke American intervention and use Mexican nation-

al feeling to depose Carranza. Villa’s intimate knowledge of the terrain and his widespread popular support

in northern Mexico allowed him to escape the grasp of General Pershing’s Punitive Expedition, but Carranza

was much too wily to side with the Americans. Pershing thus lost militarily, while Villa lost politically.

Resentment over Wilson’s action contributed to the arrest in February of American sailors by followers of Huerta in the port of Tampico. Although the sailors were soon released with an expression of regret from Huerta, Rear Adm. Henry T. Mayo, commanding the American Fleet in the area, demanded a public apology. Huerta refused. Feeling that intervention was unavoidable and seeing an opportunity to deprive Huerta of important ports, President Wilson supported Admiral Mayo and proposed to occupy Tampico, seize Veracruz, and blockade both ports. When a German steamer carrying a cargo of ammunition arrived unexpectedly at Veracruz in late April, the United States put ashore a contingent of marines and sailors to occupy the port and prevent the unloading of the ship. Naval gunfire checked a Mexican counterattack and by the end of the month an American force of nearly 8,000 (about half marines and half Army troops) under the command of Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston occupied the city. For a time war with Mexico seemed inevitable, but both Wilson and Huerta accepted mediation and the Mexican leader agreed to resign. Carranza had barely had time to assume office when his erstwhile ally, Francisco "Pancho" Villa, rebelled and proceeded to gain control over most of northern Mexico.

Despite the precariousness of Carranza’s hold on Mexico, President Wilson decided to recognize his government. It was now Villa’s turn to show resentment. He instigated a series of border incidents that culminated in a surprise attack by 500 to 1,000 of his men against Columbus, New Mexico, on March 9, 1916. Villa’s troops killed a substantial number of American soldiers and civilians and destroyed considerable property before units of the 13th Cavalry drove them off. The following day President Wilson ordered Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing into Mexico to assist the Mexican government in capturing Villa.

On March 15 the advance elements of this punitive expedition entered Mexico in "hot pursuit." For the next several months Pershing’s troops chased Villa through unfriendly territory for hundreds of miles, never quite catching up with him but managing to disperse most of his followers. Although Carranza’s troops also failed to capture Villa, Carranza soon showed that he had no desire to have the United States do the job for him. He protested the continued presence of American troops in Mexico and insisted upon their withdrawal. Carranza’s unfriendly attitude, plus orders from the War Department forbidding attacks on Mexicans who were not followers of Villa, made it difficult for Pershing to deal effectively with other hostile Mexicans who blocked

his path without running the risk of precipitating war. Some clashes with Mexican government troops actually occurred. The most important took place in June at Carrizal, where scores were killed or wounded. This action once again created a critical situation and led President Wilson to call 75,000 National Guardsmen into federal service to help police the border.

Aware that the majority of Americans favored a peaceful solution, Wilson persuaded Carranza to resume diplomatic negotiations. The two leaders agreed in late July to submit the disputes arising out of the punitive

expedition to a joint commission for settlement. Some time later the commission ruled that the American unit commander in the Carrizal affair was at fault. Although the commission broke up in January 1917 without reaching agreement on a plan for evacuating Pershing’s troops, relations between the United States and Germany had reached so critical a stage that Wilson had no alternative but to order withdrawal of the punitive expedition.

Pershing failed to capture Villa, but the activities of the American troops in Mexico and along the border were not entirely wasted. Dispersal of Villa’s band put an end to serious border incidents. More important from a military point of view was the intensive training in the field received by both Regular Army and National Guard troops who served on the border and in Mexico. Also, the partial mobilization drew more attention to the still-unsolved problem of developing a satisfactory system for maintaining in peacetime the nucleus of those trained forces that would supplement the Regular Army in national emergencies. Fortunately, many defects in the military establishment, especially in the National Guard, came to light in time to be corrected before the Army plunged into the war already under way in Europe.

America could not ignore the huge conflict raging in Europe. At various times it seemed as if the country was going to be dragged into the war, only to retreat from the precipice each time. When the Germans sank the U.S. merchant ship Gulflight on May 1, 1915 and then the British liner Lusitania a week later with the loss of 128 American lives, American public opinion finally began to recognize that the United States might have to become involved. Voices calling for more preparedness began to seem more sensible.

J OHN J. P ERSHING (1860–1948)

Pershing was often referred to as Black Jack Pershing, though the nickname’s origins are in doubt. His

leadership of the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, a colored unit, may have led to the harsh epithet; though

he had previously taught at a school for African Americans near his hometown of Laclede, Missouri, which

also could have been the nickname’s genesis. His pacification successes in the Philippines from 1901−1903

led to his direct promotion by President Theodore Roosevelt from captain to brigadier general and his ap-

pointment as Governor of Mindanao, where he served from 1906 to 1913. He did not get along well with

everyone, though; his battles with Chief of the War Department General Staff Peyton C. March over who

was in control of the Army during World War I would lead to factions within the Army. His promotion after

World War I to the unique rank of General of the Armies would cap an unusual career.

Among the voices were those of former Secretary of War Elihu Root, ex-President Theodore Roosevelt, and former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. Another was that of General Wood, whose term as the Army’s Chief of Staff had expired just over a year after President Wilson and his peace-oriented administration had come to office. Following a practice he had introduced while Chief of Staff of conducting summer camps where college students paying their own way could receive military training, Wood lent his support to a similar four-week camp for business and professional men at Plattsburg Barracks, New York. Known as the Plattsburg idea, its success justified opening other camps, assuring a relatively small but influential cadre possessing basic military skills and imbued with enthusiasm for preparedness.

Yet these were voices of a heavily industrialized and articulate east. Few like them were to be heard from the rural south, the west, or a strongly isolationist midwest where heavy settlements of German-Americans (called by some, derisively, hyphenated Americans) detected in the talk of preparedness a heavy leaning toward the nation’s historic Anglo-Saxon ties. There was in the country a strong tide of outright pacifism, which possessed an eloquent spokesman in Wilson’s Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan.

The depth of Bryan’s convictions became apparent in the government’s reaction to the sinking of the Lusitania. Although Bryan agreed with the President’s first diplomatic protest over the sinking, he dissented when the President, dissatisfied with the German reply and determined to insist on the right of neutrals to engage in commerce on the high seas, insisted on a second and stronger note. The Secretary resigned.

Although sinkings by submarine continued through the summer of 1915, Wilson’s persistent protest at last produced an apparent diplomatic victory when in September the Germans promised that passenger liners would be sunk only after warning and with proper safeguards for passengers’ lives. Decelerating their campaign, the Germans actually acted less in response to American protests than to a realization that they lacked enough submarines to achieve substantive victory by that means that would outweigh the diplomatic cost.

American commerce with Europe meanwhile continued, particularly in munitions; but because of the British blockade almost all was with the allied nations. The British intercepted ships carrying foodstuffs to Germany and held them until their cargoes rotted. Just after mid-1915 they put even cotton on a long list of contraband and blacklisted any U.S. firm suspected of trading with the Central Powers. These were deliberate and painful affronts, but so profitable was the munitions trade that only the southern states, hurt by the loss of markets for cotton, raised loud protest. In October 1915 President Wilson repealed a ban earlier imposed on loans to belligerents, thereby further stimulating trade with the Allies.

While Americans as a whole remained opposed to entering the war, their sympathy for the allied cause grew. A combination of allied propaganda and German ineptitude was largely responsible. The propagandists were careful to ensure that nobody forgot the German violation of Belgian neutrality, the ordeal of "Little Belgium." Stories of babies mutilated and women violated by German soldiers were ram

pant. The French executed nine women as spies during the war; but it was the death of a British nurse, Edith Cavell, at the hands of the Germans that the world heard about and remembered. Clumsy German efforts at propaganda in the United States backfired when two military attachés assigned to posts in America were discovered financing espionage and sabotage. The Germans did their cause no further good in October 1916 when one of their submarines surfaced in Newport Harbor, sent an officer ashore to deliver a letter for the German ambassador, then submerged and sank nine allied ships close off the New England coast.

Continuing to champion neutrality and seeking—however unsuccessfully—to persuade the belligerents to establish international rules of submarine warfare, President Wilson was personally becoming more aware of the necessity for military preparedness. Near the end of a nationwide speaking tour in February 1916, he not only called for creation of "the greatest navy in the world" but also urged widespread military training for civilians, lest some day the nation be faced with "putting raw levies of inexperienced men onto the modern field of battle." Still upholding the cause of freedom of the seas, he refused to go along with congressmen who sought to forbid Americans to travel on armed merchant ships.

Wilson nevertheless continued to demonstrate a fervent hope for neutrality. A submarine attack in March on the French steamer Sussex with Americans aboard convinced the President’s adviser, Edward M. "Colonel" House, and his new Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, that the nation should sever diplomatic relations with Germany. A fiery speech of self-justification by the German chancellor in the Reichstag and a cynical reply to an American note of protest did nothing to discourage that course. Wilson went only so far as to dispatch what amounted to an ultimatum, demanding that the Germans cease the submarine war against passenger and merchant vessels or face severance of relations with the United States.

While questioning the American failure to deal as sternly with the British blockade and rejecting the charge of unrestricted submarine warfare, Germany again agreed to conform to American demands for prior warning and for protecting the lives of passengers. Wilson in turn saw that unless something could be done about the British blockade the German vow probably would be short lived. When a protest to the British availed nothing, the President offered the services of the United States to negotiate a peace. That brought little positive response from either side.

The National Defense Act of 1916

Some of the President’s growing inclination toward the cause of preparedness could be traced to increasing concern on the part of members of his administration, most notably the Secretary of War, Lindley M. Garrison. As an annex to the Secretary’s annual report in September 1915, Garrison had submitted a study prepared by the General Staff entitled, "A Proper Military Policy for the United States." Like proposals for reform advanced earlier by Stimson and Wood, the new study turned away from the Uptonian idea of an expansible Regular Army,

which Root had favored, to the more traditional American concept of a citizen army as the keystone of an adequate defense force. Garrison proposed more than doubling the Regular Army, increasing federal support for the National Guard, and creating a new 400,000-man volunteer force to be called the Continental Army, a trained reserve under federal control as opposed to the state control of the Guard.

Although Wilson refused to accept more than a small increase in the Regular Army, he approved the concept of a Continental Army. Garrison’s proposal drew support in the Senate, but not enough to overcome adamant opposition in the House of Representatives from strong supporters of the National Guard. Influential congressmen countered with a bill requiring increased federal responsibility for the Guard, acceptance of federal standards, and agreement by the Guard to respond to a presidential call to service. Under pressure from these congressmen, Wilson switched his support to the congressional plan. This, among other issues, prompted Garrison to resign.

There the matter might have bogged down had not Pancho Villa shot up Columbus, New Mexico. Facing pressing requirements for the National Guard on the Mexican border, the two halls of Congress at last compromised, incorporating the concept of the citizen army as the foundation of the American military establishment but not in the form of a Continental Army. They sought instead to make the National Guard the nucleus of the citizen force.

Passed in May and signed into law the next month, the bill was known as the National Defense Act of 1916. It provided for an army in no way comparable to those of the European combatants and produced cries of outrage from those still subscribing to the Uptonian doctrine. It also contained a severe restriction inserted by opponents of a strong General Staff, sharply limiting the number of officers who could be detailed to serve on the staff at the same time in or near Washington. The bill represented nevertheless the most comprehensive military legislation yet enacted by the U.S. Congress. The National Defense Act of 1916 authorized an increase in the peacetime strength of the Regular Army over a period of five years to 175,000 men and a wartime strength of close to 300,000. Bolstered by federal funds and federal-stipulated organization and standards of training, the National Guard was to be increased more than fourfold to a strength of over 400,000 and obligated to respond to the call of the President. The act also established both an Officers’ and an Enlisted Reserve Corps and a Volunteer Army to be raised only in time of war. This provision expanded the Medical Reserve Corps, established in 1908, into a full-spectrum federal reserve force that would mobilize and train over 89,476 officers during World War I. To accomplish this, the act created a new Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program to establish training centers for officers at colleges and universities.

Going beyond the heretofore-recognized province of military legislation, the National Defense Act of 1916 also granted power to the President to place orders for defense materials and to force industry to comply. The act further directed the Secretary of War to conduct a survey of all arms and munitions industries. A few months later the Congress demonstrated even greater interest in the industrial aspects of defense by creating the civilian Council of National Defense made up

of leaders of industry and labor, supported by an advisory commission composed of the secretaries of the principal government departments, and charged with the mission of studying economic mobilization. The administration furthered the preparedness program by creating the U.S. Shipping Board to regulate sea transport while developing a naval auxiliary fleet and a merchant marine.

An End to Neutrality

As a new year of war opened, German leaders decided that they had lost so many men at Verdun and on the Somme that they would have to assume the defensive on the Western Front; their only hope of quick victory lay with the submarines, of which they now had close to 200. By operating an unrestricted campaign against all shipping, whatever the nationality, in waters off the British Isles and France, the Germans believed they could defeat the Allies within six months. While they recognized the strong risk of bringing the United States into the war by this tactic, they believed they could starve the Allies into submission before the Americans could raise, train, and deploy an Army. They were nearly right.

The German ambassador in Washington continued to encourage Wilson to pursue his campaign for peace even as the Germans made their U-boats ready. On January 31, 1917, Germany informed the U.S. government and other neutrals that beginning the next day U-boats would sink all vessels, neutral and allied alike, without warning.

While the world waited for the American reaction, President Wilson searched for some alternative to war. Three days later, still groping desperately for a path to peace, he went before the Congress not to ask a declaration of war but to announce a break in diplomatic relations. This step, Wilson hoped, would be enough to turn the Germans from their new course.

Wilson could not know it at the time, but an intelligence intercept already had placed in British hands a German telegram that when released would remove any doubt as to German intentions toward the United States. This message was sent in January from the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German ambassador to Mexico, proposing that in the event of war with the United States, Germany and Mexico would conclude an alliance with the adherence of Japan. In exchange for Mexico’s taking up arms against the United States, Germany would provide generous financial assistance. Victory achieved, Mexico was to regain her lost territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Cognizant of the impact the message was bound to have on the United States, the British were nevertheless slow to release it; they had to devise a method to assure the Americans of its authenticity while concealing from the Germans that they had broken the German diplomatic code. On February 23, just over a month after intercepting the telegram, the British turned over a copy to the American ambassador in London.

When President Wilson received the news, he was angered but still unprepared to accept it as cause for war. In releasing the message to the press, he had in mind not inciting the nation to war but instead moving

In exchange for Mexico’s tak-

ing up arms against the United

States, Germany would provide

generous financial assistance.

Victory achieved, Mexico was

to regain her lost territories of

Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Congress to pass a bill authorizing the arming of American merchant ships, most of which were standing idle in American ports because of the submarine menace. As with the break in diplomatic relations, this, the President hoped, would so impress the Germans that they would abandon their unrestricted submarine campaign.

Congress and most of the nation were shocked by revelation of the Zimmermann message; but with their hopes for neutrality shattered, pacifists and pro-Germans countered with a roar of disbelief that the message was authentic. Zimmermann himself silenced them when in Berlin he admitted to having sent the telegram.

In the next few weeks four more American ships fell victim to German U-boats. Fifteen Americans died. At last convinced that the step was inevitable, the President went before Congress late on April 2 to ask for a declaration of war. Four days later, on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany: a war for which the U.S. Army was far from being prepared.

The Army Transformed

The years 1902 to 1917 saw the United States entering fully upon the world stage, and that entrance mandated that the Army change itself accordingly. The Army was forced to shed most of its Indian-fighting past and transform itself into an Army for an empire. As an imperial police force it pacified the Philippines, occupied Cuba and Puerto Rico, and participated in the international intervention force into China during the Boxer Rebellion. At the same time, it continued to fulfill its obligations as a homeland security force as it conducted operations along the southern border of the United States and into Mexico itself. The Army had by necessity become a much more capable force than ever before, equipped for overseas expeditions and for the essentially constabulary duties of America’s new empire.

Although the Army was forced to make numerous practical changes to cope with the new challenges of America’s becoming a world power, it also underwent a series of intellectual changes that established a framework for even greater changes to come. At the heart of these changes were the reforms undertaken by Secretary of War Root during his years in office (1899–1904). These Root reforms (changing the command structure of the Army with the establishment of the office of Chief of Staff with a General Staff and breaking the power of the bureau chiefs; the creation of the National Guard with training, organization, and equipment in line with the Regular Army; and the reorganization of the Army school system including the establishment of the Army War College in 1903) were essential in increasing the professionalism of the Army and forcing it to look outward to the new challenges to come.

Thanks to the reforms of the early twentieth century, for the first time the Army would have some of the basic intellectual and procedural tools in hand to prepare and conduct contingency plans for a wide variety of operations. It would have a corps of regular officers and men supported by a National Guard available for federal service on relatively short notice. When the National Defense Act enhanced the reforms in 1916, the result was little short of revolutionary. The Root reforms laid the basis for transforming the Army into a modern, albeit

still modestly sized military force suitable for the new missions that had to be performed.

Yet events outside the United States were moving quicker than any peacetime reform packages could hope to contain. The United States’ involvement in the war in Europe would shortly mandate the wholesale remaking of its Army yet again. This massive conflict that began in 1914 in Europe was to change all of America’s assumptions when it came to armies and international commitments. The war was terrifying to behold, with million-man armies locked in deadly combat in trenches that scarred hundreds of miles of the landscape of northern France. Deadly armies of conscripts equipped with machine guns, vast arrays of artillery, airplanes, and tanks showed to any intelligent observer how ill prepared the American Army would be for the challenges of modern warfare. A new, and severe, test for American arms was on the horizon.

D ISCUSSION Q UESTIONS

1. What lessons do you believe the U.S. Army should have been able to use from its Indian-fighting days in the new situation of policing an empire?

2. Why was the Army so slow to adopt new technology even in the face of dramatic changes in the scope and scale of European warfare?

3. Of what value were the Root reforms? Why did a civilian Secretary of War have to implement these reforms rather than the senior Army uniformed leadership?

4. What was the "Plattsburg idea," and how influential do you think it was?

5. Was the United States justified in intervening in Mexican affairs in 1916? What were some of the unintended consequences for the U.S. Army as a result of this expedition?

6. Should America have entered World War I? How could it have been avoided?

R ECOMMENDED R EADINGS

Abrahamson, James L. America Arms for a New Century: The Making

of a Great Military Power. New York: Free Press, 1981.

Ball, Harry P. Of Responsible Command: A History of the U.S. Army

War College. Carlisle Barracks, Pa.: Alumni Association of the U.S.

Army War College, 1983, chs. 1–7.

Challener, Richard D. Admirals, Generals, and American Foreign

Policy, 1898–1914. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Finnegan, John R. Against the Specter of a Dragon: The Campaign

for American Military Preparedness, 1914–1917. Westport,

Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1974.

Hewes, James E., Jr. From Root to McNamara: Army Organization

and Administration, 1900–1963. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army

Center of Military History, 1983.

Lane, Jack C. Armed Progressive: A Study of the Military and Public

Career of Leonard Wood. San Rafael, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1978.

Leopold, Richard W. Elihu Root and the Conservative Tradition.

Boston: Little, Brown, 1954.

Morison, Elting E. Turmoil and Tradition: A Study of the Life and

Times of Henry L. Stimson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960, chs.

9–15.

Nenninger, Timothy K. "The Army Enters the Twentieth Century,

1904–1917," in Against All Enemies: Interpretations of American

Military History from Colonial Times to the Present, ed. Kenneth

J. Hagen and William R. Roberts. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood

Press, 1986.

———. The Leavenworth Schools and the Old Army: Education,

Professionalism, and the Officer Corps of the United States

Army, 1881–1918. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1978.

Smythe, David. Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing.

New York: Scribner’s, 1973.

Armstrong, David A. Bullets and Bureaucrats: The Machine Gun and

the U.S. Army, 1861–1916. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press,

1982.

Beale, Howard K. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to

World Power. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

Clendenen, Clarence C. Blood on the Border: The United States Army

and the Mexican Irregulars. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

Detrick, Martha. The National Guard in Politics. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 1965.

Deutrich, Mabel E. Struggle for Supremacy: The Career of General

Fred C. Ainsworth. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1962.

Langley, Lester D. The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in

the Caribbean, 1898–1934. Wilmington, Del.: SR Books, 2002.

Linn, Brian. Guardians of Empire: The U.S. Army and the Pacific,

1902–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

McCullough, David. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the

Panama Canal, 1870–1914. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1977.

Millett, Allan R. The Politics of Intervention: The Military Occupation

of Cuba, 1906–1909. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1968.

Reardon, Carol. Soldiers and Scholars: The U.S. Army and the Uses

of History, 1865–1920. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas,

1990.

Skowronek, Stephen. Building a New American State: The Expansion

of National Administrative Capacities, 1877–1920. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1982, chs. 1, 2, 4, 7, Epilogue.